Episode 7: Luis Patricio Wants to Cure "Car Brain"

One of Joe's favourite subjects is bicycles, and who better to discuss it with than Luis Patricio, a professor and PhD student specializing in urban studies.

Video

Audio

Episode Synopsis

One of Joe's favourite subjects is bicycles, and who better to discuss it with than Luis Patricio, a professor and PhD student specializing in urban studies. Joe and Luis explore the profound impacts of car-centric urban design and introduce concepts like "mobility poverty," "moto-normativity," and "car brain," highlighting how car-dominated infrastructure limits access to essential resources, fosters inequality, and disconnects communities. The conversation delves into the environmental, social, and economic benefits of shifting toward more sustainable transportation models, including protected bike lanes, public transit, and the 15-minute city concept. Luis shares personal insights on how cycling fosters community connections and discusses the transformative potential of reimagining urban spaces—like converting parking lots into community hubs or urban farms. This thought-provoking discussion challenges conventional ideas about transportation and invites listeners to envision cities designed for people, not just cars. Tune in for an inspiring look at building equitable, vibrant urban environments.

Links Mentioned In The Episode

Episode Transcript

JOE:

Quick note about this episode before we dive in.

HOLLY:

This interview...

JOE:

And the intro-

HOLLY:

Were recorded before Ontario passed new bike lane legislation.

JOE:

So we'll offer Louise an opportunity to address this in a blog post or a future episode of the podcast.

HOLLY:

But for now, enjoy one of our most intense episodes.

HOLLY:

JOE, how many bicycles do you own?

JOE:

18

HOLLY:

Oh my God. Are you serious? When did this obsession begin?

JOE:

Jeez, Louise. My wife thinks I have a bit of a problem.

HOLLY:

Yeah, I would agree with her. I would agree with her.

JOE:

From webisodes. This is Globality, a podcast at the intersection of urban agriculture, food security and community.

HOLLY:

On this episode, Joe sits down with Luis Patricio, who is very much not an avid cyclist.

JOE:

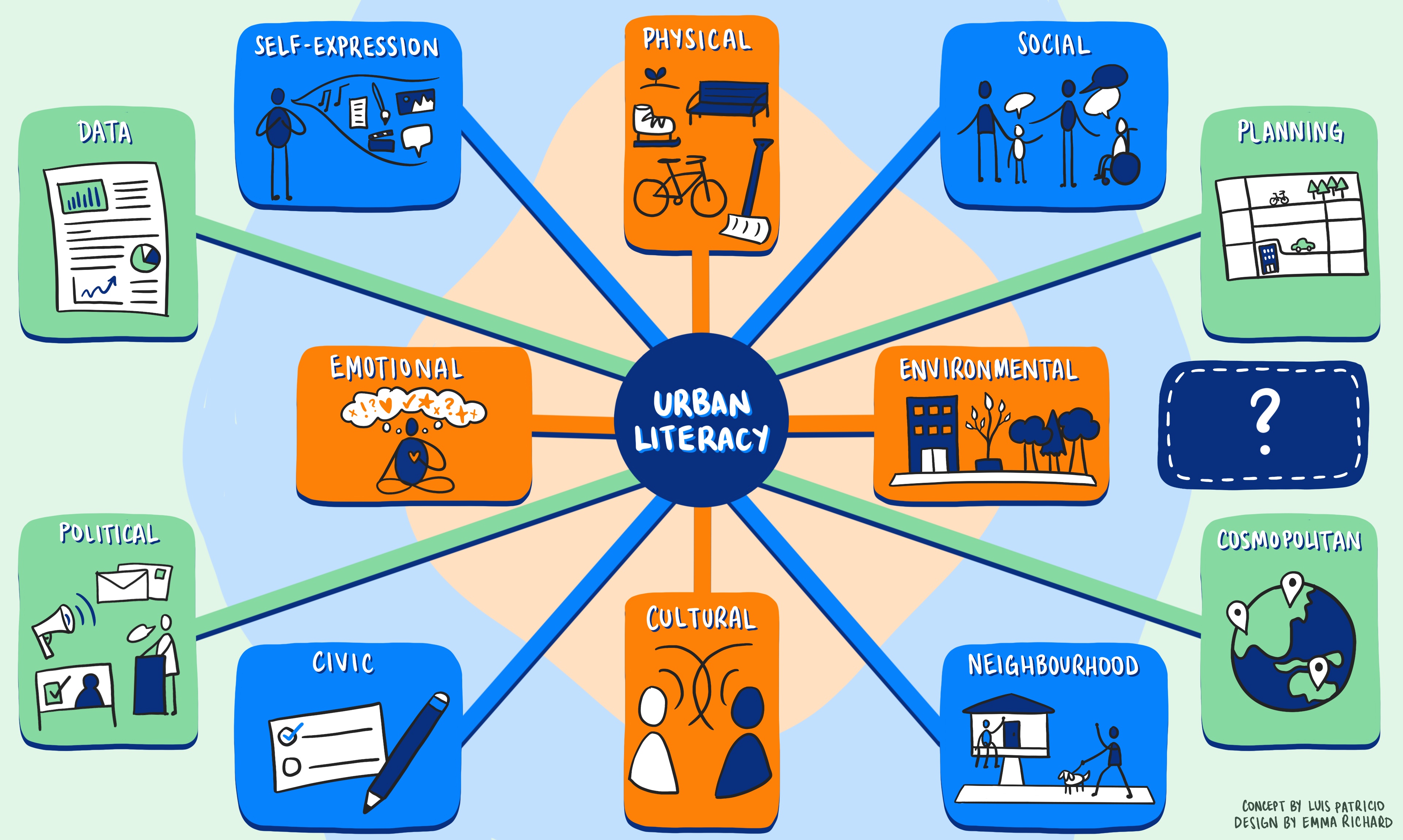

Luis is a professor and a PhD student in urban studies, and focuses his research on urban design and what he calls mobility poverty.

HOLLY:

This was definitely our most controversial episode so far. I have learned a few favorite terms from your conversation with Luis.

JOE:

Oh yeah. Like what?

HOLLY:

Moto Normativity and Carb Rain are now in my daily vocab, but I was worried at the start that we would be talking about bicycles most of the time.

JOE:

To be honest, me too. But Luis really ends up describing how a car focused transportation design affects everything from community to access to healthy food. He even brought a brochure on his research to the interview.

HOLLY:

Is that what was on the table in front of him?

JOE:

Yeah. Sadly, we didn't get to that.

HOLLY:

Well, if you're watching or listening to this and have thoughts to share, send your questions, ideas and suggestions for future shows to Joe at Gro pod.com.

JOE:

Siskins, the law firm, hosts this near beautiful office for this interview. So huge thanks for letting us use the space.

HOLLY:

And now grip those handlebars tight and get ready for a wild ride. Through Joe's conversation with Luis Patricio.

JOE: Luis, there are so many reasons I've been really looking forward to this conversation, but my number one reason is that I get to nerd out with somebody about bicycles.

LUIS:

Thanks for having me, Joe.

JOE:

My pleasure. We're going to give the audience some background on you in a separate intro, but since your bicycle is featured in the room with us, you describe yourself as a person who rides a bicycle. Do you ever refer to yourself as a cyclist? And is there a difference between the two?

LUIS:

I don't generally refer, to myself as a cyclist. I don't think as as being a cyclist, but I understand that a lot of people do say that. And usually when they, you know, like, whatever they, they call me for an interview or something. They always say the avid is not just a cyclist. Right? Is the avid cyclist?

JOE:

Yes.

LUIS:

I am starting to get a little itchy with, like, I just ride my bike. Like you would not say the avid driver. Whatever, Michael. Something, something. The person just drives the car to get whatever they need to get to. And this is how I see myself, right? But at the same time, I understand that, it's such a different way in North America to get to places that people tend to merge those two things, right? Like merge that make that identified a bigger part of my identity than what it is for today.

JOE:

We'll call you Louis. Okay. So the last hundred years have been very car centric. What is why is that a problem?

LUIS:

Why is that a problem? And I think that's the key word you just said is centric, right? And in many times, and you hear the pushback like you're it's a war on cars. Like you want to get rid of all the cars. Like, how are we going to get around? It's not about getting rid of all the cars or, it's about balancing things. There are so many reasons why being car centric is a problem, and I think it's important to have a good understanding, like a broad, broader understanding of that, because then you get to solutions like, oh, let's just has electric vehicles and everybody will be happy. Well, if you have over a million people getting killed on the roads, and 100% or almost 100% of those, accidents, quote unquote, those casualties are, involved, are involving cars. If they're electric, we still have that problem, right? Like, obesity. If you're not taking active transportation, if you're not doing physical activity to get around, you still have the problems. You have electric vehicles. The way that we developed their city, like urban sprawl and how far we need to go and and sometimes a lot of people can go to places, if you're electric vehicles, actually, you're making this problem even harder because they are more expensive. And even when it comes to the environment, one of the less intact ecosystems on the planet, the deep seas. Now you're talking about, like a literally a race to the bottom to get to those minerals, to have enough materials to build batteries for cars. So we're talking about destroying an ecosystem that we don't even know what it's there just to perpetuate a car centric way of living. And, I could go on, but I think I, you know, we got a good sense of why we need to give more space for other modes of transportation.

JOE:

And we are going to go on. So this is good. And now all that being said, do you feel that there's an adversarial, relationship between people who drive cars and people who ride bicycles?

LUIS:

I think there is an underlying and it's interesting that that people has been researching this now, and they have a name for it. And it's, I think, naming is very powerful. Yeah. They call it the car brain.

JOE:

Okay.

LUIS:

And there's a more scientific term, if you will. That is motor normativity. What that means is that the way that people think about in car centric places, which is a lot of cities around the world, but very strong in North America. The way that people think about cars and they have, a value judgment about what you can you can't do with when you're using a car is different. ,Is different from everything else. Right. One quick example. If you say what you think is reasonable and acceptable to use public space to store private property, can you do that? Is that okay? Framing that way, most people say like, of course, no, it's public. You shouldn't just put your stuff there like it. You know, like it's public money. You you can't. And then you ask the question, what do you think about free parking on the streets? Should we have that or not? Okay. The answers will be dramatically different. There will be many more people. There will be in favor. And like, really strong supporters of free parking, when all that that is, is story private property in a public space. So this is one example of when you're talking about cars. Our brain shifts completely the way that we think. And I think that underlies your answer. Back to your question, I think that underlies how conversations between people who usually drive and people who usually ride a bike can be so adversarial because they're they're coming from very different places. And I'd say even people who are cycling, if they live in a car centric society, they will have that bias as well.

JOE:

So they will adopt a car brain.

LUIS:

They will have a protection brain. Yes, yes. They will accept that. For example, free parking is something that it's okay. They would accept that when they're crossing the road, they're gonna yield to the driver. They will accept that, even when you're walking on the on the streets and you see a no exit sign, that sign makes sense. I would argue it doesn't. Many cases there is an exit right? If you can walk or bike, that will. There will be an exit. Like hardly is the case. There's actually like a wall that you can't go through. So they no exit and and the way that the just a small example, but the whole way that the cities the city is built and design is with that car brain in mind is from the perspective of people driving cars. When we talk about, oh, they close the streets for a party, there is a thousand people in the streets. What do you mean, they're close there. The street is open, right? Again and. But but again, even if you're a pedestrian of cyclists, you would use the language, they'd close the street and you just feel normal because you're walking from a car. You're using your car brain, right? They open the street, right? Not they close the street.

JOE:

So people on the streets, natural.

LUIS:

For the most part of human existence, like hundreds, thousands of years, the street was a place for, doing business to meet friends, to socialize, to, you know, markets, celebrations, sign your partner games. Like everything. Street is the is is what, urban street primarily is what makes cities what they are. Cities are a place where you can have, many people from many places doing different things. The biggest attraction of cities is other people. And people that can, that need and can offer different things. And the street, the public street was the epitome of it. Was this the manifestation of that right is when people actually came together. And as you're saying, right at the last hundred years when you have a car centric human form, then you divide the street of most of almost every use that they had for thousands of years and become just this right of way. It's just just a no man's land, right? Like you're supposed to use the street just to get from from a from point B, and primarily by driving or using a motorized vehicle like that. There is still many people who believe that cars don't, sorry, bicycles don't belong on the roads. Just the cars. When you know that, in many legislations, not only they should be there, but they should be prioritized and respect and get the right of way in many ways.

JOE:

You use the term mobility poverty. Can you talk me through that concept?

LUIS:

Yeah, that's that's a great question. And, I am so interested in that question that I actually started PhD at Western University to explore that, that question. So I'll be for the next four years, I'll be taking a much deeper dive on the topic. And I think this is a great Segway. Because we just talking about the car centric, the car brain. Right. And mobility, poverty is or or transport poverty is the limitation that people have to access what they need. And usually when we talk about accessibility, we're talking, about wheelchairs and that kind of thing, like accessibility of places. I'm talking about accessibility in a much larger, right, open context. Accessibility in the sense of being able to get to work, being able to get to school, the being able to get to a friend's house, to nature, to parks, to the beach in the summer, to a grocery store and and and and acquire healthy foods and everything else you can imagine places of worship. When we build cities with our car brain, when we build urban spaces, there are car centric. We exclude so many people. There is a book that was published, I think this year, maybe last year I think was this year that is called when driving is Not an option and it's an American book. So it's about, the United States, but even the United States. The book is saying that a third of people actually don't drive a third, a third. So if you think about it, we're designing and allocating resources, and we are excluding from the get go 30. That's a huge number.

JOE:

So huge number.

LUIS:

30% of the population. And in general, we're talking about the most vulnerable vulnerable groups. And you can think about any dimension you're thinking about is thinking about age. So you're talking about souls who are under 16. And they would love to go to their friend's house or, you know, to the gym or whatever on their own and not have to wait every time to be driven by their parents, or you're talking about senior, citizens that might not be able to drive anymore. And and there's a lot of research on that. That is it's almost like a death penalty. In North America, when you live their whole life, being able to drive and get to places and all of a sudden you can't, right? Because of physical or financial whatever situations. And you think about newcomers or people of color or people with, physical disabilities that don't, can't drive because they can't see. So all if you put all those groups together, they, they are close to the 50% in some cases, even the majority of the population. And you're not catering to all of them. So mobility, poverty or transport poverty is is that limitation that excludes people to get. And and here in London is tragic. Actually I was going to say funny, but it's actually tragic that there's so many even job posts that one of the last line is, access to a vehicle, right? Or having a driver's license. I would understand if you're hiring a driver. So it's part of the job. But those are jobs. Those are office jobs, right? And they say if you don't have a driver's license, you can't get a job. It doesn't matter how much experience you have, it doesn't matter your background. If you don't have a car, you don't belong in the society. You don't have access. You don't have the right to even apply to this job. So this is a little bit of what transport, justice is.

JOE:

So how does moving away from a car centric community build community? When we take the car out of the equation, how does that build community?

LUIS:

Yeah. That's a great question. And again, we can we can the car can have a smaller role, but the car is still part of the equation. Right. Again, it's not a all or nothing. There is there is a place, to have cars and has, personal motorized transportation, but much, much less. And as cyclists, we, we kind of know that some of the answers to that question, right.

JOE:

We've done the research.

LUIS:

Yeah. Well, from from just from lived experience riding of individual, standpoint, the connection that you can build with people and your surroundings is so much tighter is so much deeper. I, I did you're saying like we did the research and actually I did kind of a personal experiment. I, I was counting how many people smiled to me on my way to work, and I was biking, and I counted for 2 or 3 months every day. And on average, I would get seven eight smiles every day. And by as much as I mean, if you just, you know, just biking by and and people and you're slow enough that people can actually look in your face and they'll give you, you know, just little nod and like, a little bit like just a quick smile. And I think that alone in a society that is becoming more and more polarized, that it's hard to see each other just being able to be in a public space with others and have that those, there's a guy from, from London here that talks about micro neighborliness. And I think this is like a great example of what that is. Right? It's just and some of those people were the same people over and over again. And like when I'm riding the bike with my kids, they would remember the kids the day they would I didn't have the kids like, hey, you forgot someone like what happened? And you know that those little jokes, on a daily basis, I think can really make your day just build and community just building community, you know, it's a friendly face, the familiar face. And it might sound like a small thing, but if you think of thousands of people, be able to experience that on a daily basis, when you add that up, it really makes a big difference. And then when we think about the some of the challenges that we have when the car centric society, when we have the car as a small part of the equation, you would have, more space, right? Here in London, for example, it's a very there's a, a podcast. I not associated with the guy in any way, but it is an interesting podcast. It's called Not Just Bikes. He's from London now, lives in the Netherlands. Very interesting. Yeah. And he uses London as one of his examples of how not.

JOE:

He does do that.

LUIS:

Build the city. So in cities like London, for example, you would have in some neighborhoods more than 50% of the area, like the whole land or urban land dedicated to cars in forms of like roads, parking lots, gas stations and you name it, everything. So if you think about it, if you have less need for cars and your your focusing on bikes and public transit, think about all we could do with that space. They shouldn't be housing the most, the main use of land or, I don't know, education or work or productive things. Instead of just spaces where we can either store cars or move them around. So shifting away and again, like with the car brain, it's hard to think, how does that look like if you don't have a car? It does feel like the death penalty. You're like, oh my God, I can't do anything but you. You actually have examples in other parts of the world where you have public transit that is efficient, that comes every five minutes. Like honestly waiting, waiting five minutes. Is it that bad? And if you have enough public transit and you're not crowded in the bus, is it really that bad? And if you can have, you know, a super safe, protected bike lane, if you don't want to wait five minutes but you know you're going to be safe, is it really that bad? So there's many, advantages economic, social, environmental benefits to moving away from the car centric. But it does take, I think sometimes like seeing is believing, right? I wish I could just, you know, pay a ticket for everyone to go to some of those countries, like, you know, visit Copenhagen or Amsterdam and, and just see for themselves what it looks like, city that doesn't, you know, need to have all that many cars tomorrow is world car free day. Yep. And, their, their cities and car free days. Actually, a living lab. That's what it is.

JOE:

It is.

LUIS:

Is supposed to be, experiments or you, like, train things that hopefully can be permanently implemented, like it's the just become part of the city and in, in in Bogota, for example, they close quote unquote so many roads for cars, which means that people can walk and bike for hundreds of kilometers and they put more busses because a lot of people drive and they can't drive anymore what they're going to do. So they actually create alternatives for people to get around. But it becomes this huge public park and it's the entire city. It's unbelievable. I think I think anyone from from here that would go to spend a water free day in Bogota would just it would it would be mind blowing for them. It's a good.

JOE:

Way. It's interesting. You mentioned 7 or 8 smiles. That sounds like a micro vacation for a lot of people on their commute to work or to school. And when you speak about mobility, poverty, I see it ties in with a lot of work that we do around food insecurity. Do you see bonds between the two? Do you see ties between the two? Do you think that there are commonalities.

LUIS:

Food and mobility.

JOE:

Food insecurity and mobility, poverty?

LUIS:

Several times, I was talking to someone who works at the food bank, and, they're saying that the bicycle to some of those people is, is is a lifeline really? They rely on the food bank on a daily basis. Some of those people, and if they have a bicycle, they can get there and back to wherever they need to go. Sometimes they don't have a place to go there. Living in, homeless situation. And they can get their own bags faster and they can carry more stuff. Right. And usually once they get a bike and we do have a good place, we have this quickly, like, go up here in town that helps, provide affordable bikes for people who don't have a lot of money to spend on, on, on transportation. If they have a bike, it's it's free. Right? Right. Even if they have to take the bus, they have to spend, they have to pay for the tickets to get their own back. And obviously if they're using the food bank, they can't afford to have a car for and then they say, well, and some of those people who don't have a bike, they sometimes they only can carry food for 1 or 2 days and maybe they can come back soon enough. So there will be actually there will be one, two days without food at all. This is one of the many links, right. Like even in I'm from Brazil. Like one link that comes to mind is like we have biofuel, right? Yes. We're actually destroying a lot of our natural, habitats so we can grow corn or sugarcane. Okay, so we can feed the cars. So there there's there's so many other ways that we can use that land to either feed people or just preserve. Right. Like the how they call the lens of the world, like the Amazon and things like that. And even and even if you think about, we're talking about using spaces, how about urban agriculture, right. Like in my, in my head, I always imagine when I go by those parking lots downtown, if they're actually farms, you know, like big long rows or farms, people coming together, community gardens instead of storing cars. We're growing food together.

JOE:

Sounds pretty good.

LUIS:

Yeah, I, I would love to see that. I would love to. Like, just throw that idea out there in the world and see if you know someone actually. Yeah. Like, let's just, you know, take a little bit of space for cars and let's feed people together.

JOE:

When parking space is a pretty good garden. Yeah. Okay. We've talked about wonderful places over the world. We've talked about struggles. There's something that can be created in any city. That's the 50 minute city. You could probably speak to it far better than I. What do you think about 50 Minute City.

LUIS:

Yeah I think it's a great idea. And I seen it being implemented in, in some cities in Europe where it came from, Spain and it is, as you're saying, it can be in terms of the amount of work and investment that it needs to happen. It depends on how the city is built. The denser it is, the easier, it is to just diverge from car centric, planning and, and create spaces for people to get around in other ways. And then the services will be already there. Right. Because the city's densest compact for other cities were more sprawled then you need a little more like the upfront investment to make things, a little tighter and just just for, to have like a, reference point. Like I said, I'm from Brazil and I come from a city that is called Curitiba. Okay. Some of the folks in, that are part of the urbanist urban planning architecture world, they heard about quality before because that's that's the birthplace of the bus rapid transit system. The first BRT in the world was implemented in Karachi, but this is back in the 70s. And Curitiba at the time had 450 ish people, which is how many people were having London right now. But could it Curitiba now currently has the greater area has 3.5 million people. Well, the city proper, like just square itself, has about 2 million now. But the area is the same as London. So in terms of space, could it? Curitiba and London has the almost the same size. But could you? Curitiba has 4 to 5 times more people than London. So when I'm talking about density and you can, you know, we can go and Google and see areas and populations that and see how how he compares. But cities in North America tend to be way more sprawl. So the 15 minute city takes a little more work to implement, but it can start as soon as we want. There are many neighborhoods in London that are dense enough to do that, and with we have a BRT that is, we're right here. Like, if you can, if you look through the windows here, you can see, some of the lines. Right, right. Unfortunately, they're just building the east and the south branches. They cancel the north and west. A great way to make a 15 minute city here, right here in London, is to actually revisit and re-implement, like, as soon as possible, get those north and west branches, up and running again.

JOE:

And for our city planners, for our community planners. Is this how we're going to address mobility, poverty, long term? The 50 minute city concept?

LUIS:

I hope so. And there is, there is a push back in North America about the concept. And I think it comes from a misunderstanding. It and I'll go back. I think it comes from the, the car brain, from really not be able to even imagine what, life where the car is not the primary mode of transportation is, we talking about here in London? We're talking about 70 to 80% of trips being made by car. I'll, I'll use security as an example again, like including Uber where you have the BRT for now, almost 50 years, 50 years. And I think more than 50 years now, I think 30, 35% of the trips are made by car. And a lot of people do use the bus rapid transit. We don't have a lot of people cycling. We don't have a lot of investment in cycling there. But then again, you have the biggest city in the world. You have Tokyo, and it's one of the, you know, mega cities, and you have 20, 24% people cycling. So it is possible even in, you know, very large, very big cities to have, to invest in active transportation, get people riding. But it got to be it has to be safe, and it has to be convenient for people like us or like middle aged man, able bodied, educated. And we just do it.

JOE:

We just do.

LUIS:

It. We just do it. And we don't. It's not really that hard for us. But when you start thinking about, you know, a newcomer who doesn't even speak English, right? Who doesn't even understand the signs. It's like the whole it's it's so many things are alien, right? Or you think about, a young mom with, you know, young kids on a bike riding at night.

LUIS:

It's like things get way more, you need to have the the level of quality to allow people to use public transit or cycling and feel safe. We can and we should do way better.

JOE:

And this brings to a good point in especially with with newcomers utilizing bicycles coming here, cars are normalized, but riding the bicycle is seen as abnormal or maybe were fringe. This is this is how is viewed. What do you think of that?

LUIS:

I agree, I see and I've worked with many organizations, right, that support newcomers, in different ways. Right. One of the ways was with the you bike co-op, and we have bikes for newcomers. And, many of these stories that we hear is that, some of the immigrants they have a different idea of what Canada is and they think, oh, I will be able to I am looking for a more sustainable lifestyle. I want to, you know, get rid of my car. And when I moved to can, I'm just going to bike or use public transit. And when they come here they just say this harsh reality, right? Right. And like I said, some of them like if I don't have a car, I can't even get a job. And, and it could be different things. Right? It's, it sometimes is I don't speak English yet. I can even take the written exam right. So I came.

JOE:

Here for a vehicle.

LUIS:

So I can get to the first stage to get a driver's license, but I can't even do that, so I had to wait. Other times. And, and in the book that we published, the, unseen commuters, we talked to a few, a few newcomers, other times they they just don't have the means to write, to have a vehicle to own a vehicle. And they those numbers and there's a we have our low income population, but newcomers are overly represented, in that way, close to 50%. So we're talking about half of the people who come to Canada that, you know, they need refugees. And sometimes they, you know, lost a lot of what they had. They really can't afford to have a car. And we are making it really hard for them to integrate. Cuz it's not only about finding a job, it's, you know, building those social relationships, going to places, joining a gym and things like that. We're making it hard for them to integrate, and we're making it hard for them to be able to, start a new life. And, you're asking about the, intersection, right? Of food and mobility. And then you see how mobility, justice and mobility, poverty overlaps with many of the other social issues. When you think about mental health, crisis, when you think about, obesity, high obesity levels, even among kids, when you think about, affordability for many things like mobility, poverty will, will be foundational to address many of those things. If we can make and and the answer is not again, it's not let's make sure that everybody can afford a car. Right. Because we know that there are many other issues with everybody having a car. The answer is like, how can we make transportation costs less? And public transit and cycling or the 15 minute city, right? Are some of the ways that we can address that. We can make transportation costs lower.

JOE:

Okay. I have a question for you talking about mobility poverty. Do you feel that people that ride bicycles and people that have physical mobility challenges have things in common.

LUIS:

The people who ride bicycles and the people who have? I think in some ways, yeah, they are invisible. I think this is one of the things that, they might have in common. Yes. How places are people in general? They just don't think about what their needs are. In, in small, in big ways, like when you think about, like, the big city wide planning, right? How, we even discuss if we're going to plow the sidewalks or not. Again, as able bodied people, you can just hop through whatever it is, go on the street for a bed and come back. But if you're in a wheelchair or if you have sight loss or any or other things, it can be hard. It's just simply and the same for cycling, right? Like this. In citywide, you can start building bike lanes, but the the network will be as strong as the weakest link right. So it doesn't matter if you have an amazing bike lane for just part of the way that you need to go, and then you throw cyclists in a busy road, it doesn't matter. Like the people are not just not going to bike, you know, like places to pick up, park your bike when you arrive to places already. It's just not is. You're just not on people's radar. When when you're using a bike to ride in the city. And I think in many ways, people with, disabilities, they're not in the radar. For, the different needs that they have. Yeah.

JOE:

Thank you. Okay, let's dream for a second. What would the ideal urban environment look like for you in the context of mobility, poverty?

LUIS:

I think we talked a lot. We touched on a lot of the things, to me is, I don't want. I don't want to sound. That is a romantic vision. That is just a going back to the past. At the same time, I don't think we are in this linear trajectory with, you know, we're just getting better and better. I think there are lessons, from our past that we can take. And I think there's technology that we should embrace and adopt what I mean by this, like what we're saying, how streets were used for so many different things, in the past. And now it's become, more and more, rare to see those things. I think to me, ideal urban space. The streets, they have that multiple use again. Right. It's one of the principles of sustainability. And permaculture is anything has multiple uses. And I think some sites, for example, the festival here in London, where you have so many different people from so different backgrounds, they all come together to the park and, you know, and you have the vendors and you have food and you have, I think, I sometimes I go to some fairs and I'm asking myself, how can we make not a big festival, not that I, you know, one to every weekend be dancing like crazy, in the streets. But how can we make this more of a reality? How can we normalize urban public spaces where we have more people coming together, and spending time together? So, ideal urban space for me is that, you know, that neighborhood where people are walking, going from their houses and, and there's like a little grocery store, a bakery, and they can get stuff, and it's easy. And there's several in every neighborhood, and, you know, there's this quirky little store. It's just like the standard. Not everybody has the same thing, but every little neighborhood has its own character and identity, and and people have more dignity because they don't need to own a car to access all of those things. They can walk to places, they can buy to places they can take transit, and they can drive if they want. But they don't have to, they, they have a real choice. And I think one of the main things of Ideal Roman Split is face or city is, is dignity. Like, everybody just feels that they belong and they can be the best version of themselves that they want. They are encouraged and they feel that they can pursue that. Whether, you know, we're talking a lot professionally or socially or whatever it is, like your hobby, but you are even if you're not wealthy in terms of, your income, but you are able to access all of those things in the city.

JOE:

Part of community.

LUIS:

Yes. Yeah.

JOE:

People are always saying to me, I love to get rid of my car, but I can't.

LUIS:

They're right. Yeah. And when I have this conversation with other people, like when I have this conversation with friends or at a party, I would not have the conversation the same way that we're having, because I think people get defensive, quickly, like they feel guilty. And and I don't want them to feel that at all, because I understand that is hard. On on the North American city, and this is what transport justice is about. Like it is hard to, not have a car like you actually excluded. You become a second class citizen if you don't have a car, you have you have so many of so many things taken away from you. I, I wrote a blog, recently on, on my, blog post on my blog that is, about the right to enjoy the summer. Like, if you don't have a car, and you know that, like, we've been to ports, right? Like we and again, we are we are able to do that, but not everybody is. And many of the people who don't have a car, how do they go to the beach? And it's crazy to think that we had a hundred years ago, we had public transit, electric that would take a thousand people every day between London and Port Sally. Yeah, a hundred years ago. So it's not, it's not a question of do we have the technology for this to have the means? We're doing this 100 years ago...

JOE:

100 years.

LUIS:

With a thousand people every day. But now we are making different choices. We are prioritizing different things. And many people don't have access to enjoy the summer. And again, you think about the vulnerable populations and low income families that they want to you want to provide, low barrier or affordable options for them. Like, you would think that going to the beach, you know, it's a public space is free, is as big as can get. They can have as many like you can have lots of people in the beach until people just can't get there. And, you know, the city provides a lot of, options for, summer camps and things like that, but it comes with the costs.

JOE:

Of course.

LUIS:

Why can't we just go back to basics and again, access the public space where people can meet other people as equals, have that diversity? It's one. And and I keep going back to that because I think it's one of the big challenges that we have in our society today. Like people are so polarized because you're increasingly leaving your lives online using social media and it changes something in your brain when you're not actually seeing a human being, when you can actually see someone in the eyes, they have this beautiful experiment that they put someone looking each other in the eye for. I don't remember 30 seconds, two minutes, something like that. And it's impossible not to cry because that human connection is so strong. Being able to create the conditions for those human, face to face in-person interactions, even if it's not your closest friend or your family, but just to be able to be with other human beings and in a civilized way, and having fun at the beach. I think it's crucial. And we need to, rethink how we make this possible for those who would like to get there without a car because they can't drive.

JOE:

You know, I think a lot of how people use cars. It's the disconnect. It is the opposite of building community. And I would, I would really hope that that's not by design.

LUIS:

I think it's one of those. Yes and no answers. Right. I, I definitely see that part of the appeal is you all in your life. Yes. You do whatever you want. You go and leave when and where you want because you're on your own and you know, and and you can gosh, not only listen to music, but nowadays you can watch movies in your car. And don't get me started with that. But there is part of the discourse is like the car is your sanctuary and your own, your own, your independent. You own your life, you're disconnected. And it's interesting that, part as part of my, academic work with mobility and was talking to drivers and cyclists and, bus passengers. And it was so interesting to see the juxtaposition of one of the biggest concerns of car drivers. And we're, we're researching, why people choose their mode of transportation. So one of the biggest concerns of car drivers, people driving was it's unsafe. I don't feel safe if I'm not in my car, but they don't know because they are driving, right? So they are making assumptions and they are fearing something that they don't know, that they don't have the experience. And then you're talking to and those groups I'm talking about that research specifically was, employers. Yes, from the same company. So they were going to the same place and they were using the same routes. So we're talking about there is a lot of, overlap there. So and the people that walk or bike or use public transit, one of the biggest highlights, one of the big, benefits of using or biking or walking is that they were able to connect to see other people. So the very same thing that would discourage drivers to start biking was the thing that the cyclists would cherish the most. But the people who drive, they were speaking from a place of, I want to say ignorance. They okay, they didn't know what what they're talking about because they didn't try and, and many of the cyclists and that that, workplace is a place with people with me. So they're not using bikes because they couldn't afford the car. They're choosing to, to bike. They know what it is. They know they, they drove to work, a few days, but they would bike regularly once, twice a week, after being exposed, if you will, to what it is to bike to work. They didn't they didn't think was a bad thing. They actually thought it was great. It's the eight miles a day, right? They it's it's a it was the same thing for them. They were experiencing that connection with others. So I guess the question becomes, you know, if it's a selling point, I think yes, it's in some cases it's part of the, the discourse and, and, and and no, like it's unfounded. In many cases, there are missing. You're missing the fun.

JOE:

It's not quantified. Yeah. Okay. It's like what? The environment. Do you consider your. I guess in our society we call bicycle alternative transportation. Do you consider your utilization of alternative transportation a component of personal environmental stewardship?

LUIS:

100%. Yeah. And sometimes I teach environmental stewardship, at university. And, and sometimes I'm trying to give some scientific or more objective ways of showing how those things compare. Okay. One of the examples that I use is that the amount of energy that you need to drive for ten kilometers is the same amount of energy that you need to ride a bike from here to Montreal, okay? And usually people have a hard time understanding what I'm saying and accepting, but that's how much energy we need to lead a car centric, lifestyle and as as efficient as we can, as we can get on on how we, we use for transportation. Every other thing that, we need to, to, to, lead our lives. It's not just about efficiency. We really need to talk about reducing, right?

JOE:

Reducing.

LUIS:

Everybody heard about this even in school. The three R's of course, use, reuse, recycle reduces the first one. Recycle is the last resort. Reuse. This is no is a second option. The first one, when you're talking about sustainability, environmental sustainability is reduce. And the amount of energy that we use when you're driving is enormous. And there is so much that we can reduce if we're using public transit or cycling, there's so much room for improvement. So that alone and I started with energy because energy really underpins every sustainability. The reason we are smart folks, you know, humanity a whole.

JOE:

From time to time.

LUIS:

Yeah. Since sometimes they have some good ideas. You know, and have all this innovation and new technology and AI and, all this good stuff, but none of this would be possible if we didn't have such a huge, concentrated, easy to transport. Energy power, which is oil and gas right there, either in a liquid form or, you know, gas form even easier. And it's and they have such a concentrated amount and volume of power that we can the, the growth that we see in terms of population, in terms of, urban growth, right? Technology and everything else. It's primarily because we have the energy, that energy will come to an end. We already passed the peak. It doesn't mean that we were zero, but it is getting they call it the era of energy return on investment today, the energy return on investment, the energy that we get from oil nowadays is much lower than when like 56 years ago when you, you know, just tripped and there's like have a new spraying of oil and was so easy and now we have to like drill super deep or go to the ocean or it takes much more time and resources to, to get that oil than it did. And this really this really. So where do we want or not? That will be a decline in how much and and with the growing population, how much we can use. So if anything we talk about the environment, we need to have that basic understanding that we will have less energy and that we have a growth mentality because it has been this, like you mentioned, like 100 years of star centric, right? And a lot of that is tied to how much, how much more energy we had available. We had, and if you go back have like just human powered and then animal horse powered and then you have coal and then you have oil. We've been in this growth, trajectory of having more and more powerful energy sources. This will not continue forever. So the the mindset that growth is the only way and everything else is, not a desirable way to live because we can't grow, needs to change. And this underpins the, the environmental discussions is how to live. And I, I'm, I'm a firm believer that we would be much happier if you had less, you know, have those, experiments where, you know, you go to a supermarket and, and you have 30 options of strawberry jam, and you go to another one that have three, and it's so much better, like, it's easier, it's it's so overwhelming to have that many options, that people get frustrated. And sometimes there's, I don't know what to do with this. So the idea, one of the fundamental ideas when you're talking about environmental sustainability and it relates totally to, to mobility, moving on, an age of hyper mobility where you want to get faster and further, more and more is that more is not always better. There is, there is a peak, there is an ideal. And I think we, we shift away from, from that ideal.

JOE:

And we're missing things. Yeah. Okay. We we've talked about where we're going. Well, let's talk about post car society. What do you see that looking like?

LUIS:

I love the questions, Joe. I really like the questions. I like that question so much that I actually last year I ran a simulation called, Living Room series. And, I created a scenario where, we hypothetical not that crazy, but a scenario where cars would not be allowed anymore. You'd have you need to have, like, special permits if you wanted. We were talking about the emergency vehicles and this and that. But people in general, like normal citizens, would not be allowed to have a car like you have to get, you know, figured out a way. And obviously cities would have to prepare themselves to have, public transit and psych and, and all those things in, in that scenario that I was, creating and we did like, community simulation, they're 15, 20 people doing the simulation, lots of great ideas and things that I never thought about. And I think it's so important to exercise our imagination, our muscle, in that way, and really just think about out of the box and, and not assume that the way that we live today is the only way to live. But I am not so sure that in my scenario, we had time to plan. It was a collective political decision, and we have time to blend when we talk about post, car societies, we might have might not have a smooth transition. Right. And to me, my the main concern is, social justice.

JOE:

Yes.

LUIS:

So when we transition and we will, how do we ensure that those who don't have already don't have access to many things? How can you ensure that we bring this to a more balanced, state? And maybe in a way, just by not heavy, by not having, cars and automobiles, available to everyone. This will bring things so more balanced. That's my hope. Yeah. And and everything starts falling into place. If you even think about the big box stores, that you have, usually in the outskirts of the city, if you don't have the car, as you know, the primary mode of getting around 70, 80% of the people using that, like, they don't make any sense. There's so hard, like, even when you get to the parking lot, just, you know, just to get to the store is so far, and the amount of stuff that you need to, to buy, like some of those big stores and you're, you know, you should if you're whether you're biking or I. Sure. And again, we have the big bikes, right. We can carry loads and loads. But if you think about the average person, they can carry lots of bags, whether they're using public transit or a bike. Oh, the, opposed, car society is, you know, it's a society that has less big boxes. Yes, it has many more, neighborhood, local business, small stores. And the diversity in those are amazing. Like, you have the homemade local products, super unique and quirky and fun and special and and meaningful, right? It's someone who built this or no from who they bought it or it's just. It's just such a different relationship. It's things are more durable. You know, just like buying every weekend loads and loads and carts and carts. So you're, you know, you have you're on your bike, you're you're buying just what you need. Anyone buy something that lasts for a lifetime. And this is the kind it's it's funny because, probably a term that many of us heard the Anthropocene. So the idea that the human, as humans, change the Earth in such a big and dramatic way that is completely altering, global biophysical patterns. And then after that, there are like several, scenes that were created. You have the cattle scene and you can add to the scene in the Fargo scene. And one talks about the overconsumption and consumerism lifestyle. And the description of that, I think, is the Fargo scene, the description of that pinpoints the automobile, the automobile, and the suburban lifestyle as the main condition to lead, a lifestyle that is over can that is about overconsumption.

JOE:

Can I ask a question about that? Yeah. If we can't ban cars, we look at our big box stores. Can we be on the parking lots? We don't have the parking lots and we don't have the roads. Do we need the big box stores? You talked about going by what we needed. That's developing community. What are those stores look like with parking lots.

JOE:

How, how, how useful is a big box store without a parking lot.

LUIS:

Oh and I'm imagining this new future right. I imagine there's no possibility the big box stores, they really become community centers. Is they. It's one of those big shifts. And we're talking about the environmental sustainability. Right. Like the, the, the new ways of living. One of the shifts is us as consumers, to us as producers. Right. So those community centers, when we don't need to have this big box store to, you know, buy things in bulk every week, all that space available becomes, you know, like, a repair workshop where, you know, people go watch, just learn how to fix their own things. And we have a few examples here where we do have the DIY repair workshops, and we have the squeaky wheel bike co-op that you can fix your own bike, but this becomes a much bigger, undertaking. It's like a city wide spread and people, people come together again. The value of the city, right? Like people coming together, people that have many different needs and many different skill sets. So it becomes the center. Let's I know how to fix a bike, and I know how to fix a camera and I know how to fix, you know, pants and I don't know. And and and, it can be like a childcare. It can be a women's farm as well and can greenhouse because it's indoors and we have, you know, harsh winters. So it could become so many different things.

JOE:

And building community.

LUIS:

Building community, like we're coming together in those big spaces cuz as producers, not as consumers.

JOE:

So I've asked you a lot of questions. We've covered a lot of things. So anything that you'd like to cover today that we did not talk about.

LUIS:

Can can be, can I put a few personal.

JOE:

You sure can.

LUIS:

Plug about projects and ideas and things that I've been working on. So we talked a lot about, transportation and urban mobility and things like that. And I mentioned that I'm starting a PhD. One of the projects that I am working on is, and I alluded to that in our conversation, is to create a safe route for everyone from London for for sale. Yes. I think this is on the way. I think we have cycling infrastructure in London and getting to and Sunset Drive when we get reports personally is separated is on the sidewalk, but we're missing, a few, chunks in the middle. Okay. And, we had a, like, a CBC interview. And, if anyone is interested in knowing more or getting involved or supporting this, please reach out to me. We also have.

JOE:

And can I ask, how would they reach out to you?

LUIS:

So my website is luispatricio.ca And if you can share this in any way, shape or form, we can do that. Yeah, yeah. And they have, like a, contact form there. That is easy. And always I always check that form. The other one is the Vision Zero. The city adopts Vision zero, principles in 2017. I think there's a lot of work to be done to improve that. And we are hoping to put forward ideas on how to, how to advance a reminder that just a few days ago was the two year anniversary of Jim Benoit's death. Yes. He was killed on Hamilton Road, by a person driving a car. And as much as we want to find the guilty driver, I think Vision Zero, for those who don't know what it is, is a much bigger discussion. He understands that everybody fails. Yes. We. Nobody. It's whether you're a cyclist, you're a driver. Like, if you will make mistakes and we need to build and design cities that, allowed those mistakes to happen without loss of life. So there's a bigger responsibility of urban planners. So there is another project that we want to move forward is the vision Zero. Here in London again, you can read some of some of that on my website and you can reach out to me, and also on the website we like, we published. And if you want to know more about mobility, just we publish a little booklet called Unseen Commuters. Okay. And it's also you can also find that, on the website and. Yeah, like, honestly, because we talk about so many interconnections, if you feel that anything, that you're working on or many other social issues do overlap with transport, I'd love to hear from you. Like I said, I'll be doing a deep dive for the next four years of my life. Yeah, yeah, thanks for having me, Joe.

JOE:

Thank you. I have one last question. Yeah? Yeah. What keeps you growing?

LUIS:

What keeps me growing? I don't remember if I saw this on a movie or when I saw this, but it's something like it doesn't matter. We're saying, like, the alternative, right? Like we're the fringe. If if being the if being the normal is being the champion is being the popular is, being on the side of things that doesn't align with my values, like, I, I don't want to win. Like I want to be the loser, I want. I think what keeps me growing is that hope that we can normalize so many of those things. There really in many ways, there's so close. There's so close. It's really that change in mindset, in attitude. We I, I believe that we we shape we physically shape the world with our minds like a lot of and not just talking about buildings, but even every, every social contract. Like money, marriage, mortgages, like everything that only exists because it was here before. Right. So what keeps me growing? Said, you know, that that seed in my head, of the possibilities of how beautiful our lives can be, if we just want to make them. So.

JOE:

Thank you, Louise. Thank you so much for spending time with us today and being part of G

LUIS:

Yeah, thanks for having me, Joe. That was really fun.

ADAM:

GrowAbility is hosted by Joe Gansevles and Holly Pugsley and produced by Joe Gansevles and Adam caplan. Special thanks to this week's guest, Luis Patricio.

Lighting and camera design by Kevin Labonte with production support from Oliver Gansevles.

GrowAbility’s production was made much easier with the help of Jesse Chen, Terry Fujikawa, Zach Grossman, Zachary Meads, Leo Shen, and Deborah Camargo from Fanshawe College's broadcasting, television and film production program. Thanks to Janice Robinson from Fanshawe for arranging for these students invaluable participation.

Holly Pugsley of Just Keep Growing provided the plants and made sure they looked great. Audience and Marketing Strategy by Japs Kaur Miglani with support from Doruntina Uka and Tess Alcock.

Our theme music is Wandering William by Adrian Walter and can be found on Sound Stripe.

Thanks as well to Hubert Orlowski for providing technical and audio engineering advice to help our podcast sound great.

Adam Caplan - that's me - is web.isod.es executive producer and Sammy Orlowski is our senior creator.

Special thanks to Jennifer Routley from Siskinds The Law Firm for arranging to host us at their beautiful head office in downtown London, Ontario.

GrowAbility is a web.isod.es production and is produced with the support and participation of the team at The PATCH and Hutton House.